Social learning in practice

Communities of practice and legitimate peripheral participation in social pedagogy

We, as humans, are social beings and therefore, learning is an intrinsically social process. Learning takes place in many kinds of arenas where we interact with others in different contexts. We have always learned in this way, and still do – in our families, with our peers at work, in the volleyball club, while playing Counterstrike online, or as apprentices in a tailor’s shop.

Jane Lave and Étienne Wengers important work on social learning is highly relevant for practitioners of social pedagogy, because it gives us insights and ideas for how to develop models of arranged learning arenas.

Learning is a social phenomenon

Thirty years ago, Jane Lave and Étienne Wenger studied informal learning processes in diverse settings all over the world, then analysed their findings and introduced a fitting description of the phenomenon in their book: “Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation”, where they describe the dynamic learning processes which occur in “communities of practice”. They argued that learning is necessarily situated, meaning that the social context where it takes places matters. Learning occurs within authentic activity, context, and culture – and belonging to the very core of human existence.

Thus, learning is a process of participation in communities of practice, where newcomers join such communities via a process of ‘legitimate peripheral participation’, meaning that they learn by immersion in the new community. Through their participation they absorb the community’s modes of action and meaning, while they become an experienced community member.

Learning occurs within authentic activity – for example a circle of friends who love coding.

Challenging the traditional concepts of teaching and learning

Lave & Wenger’s theories challenge the traditional idea that learning is something that individuals do, that it is something that takes place inside our heads, preferably in a classroom with a teacher in front. Many of us have been led to believe that learning “has a beginning and an end; that it is best separated from the rest of our activities; and that it is the result of teaching”.

The research done by Lave & Wenger showed that learning also depends on where it takes place, and together with whom. Since we are social beings, the social context in which find ourselves matters a lot when we talk about teaching and learning.

Lave and Wenger coined the concept “communities of practice” as the place where learning happens. However, according to Wenger, “communities of practice should not be reduced to purely instrumental purposes. They are about knowing, but also about being together, living meaningfully, developing a satisfying identity, and altogether being human.”

The idea that learning takes place in social contexts, and that togetherness truly matters for teaching and learning, bring valuable insights for practitioners of pedagogy, especially when working with groups in general and how to create inclusive communities where differently abled people are welcomed, in particular.

Intuitively, we know that social connections are important to us. After all, many of us did go to school not so much to attend the lessons, but more to hang out with our friends. Thus, the concept of “communities of practice” and its major significance in all kinds of learning processes is something we know about but haven’t paid too much attention to.

Learning by legal participation

Legitimate peripheral participation (or LPP) in a community of practice allows newcomers take their first wobbly steps in the periphery of the community, because well-established old-timers tolerate the newcomers’ mistakes, and assume responsibility to bear with them, while still operating the activities of the community at full speed. It is widely accepted that it’s a learning process for everybody involved. It’s OK, or “legal” for newcomers be clueless in the beginning. It’s generally accepted, that through their participation in the activities, they will eventually learn.

Most of us can probably recall situations where we have participated in these processes – in our first job at a busy workplace, or as new members of a sports club with an age-old established culture. It took time to crack the social codes, to find one’s feet, to bring appropriate new ideas to the table and with time to become expert practitioners of the community’s main activity.

Getting to know horses and their care can be a bit daunting, at first.

Social learning in specialised pedagogical settings

The ideas around social learning, communities of practice and diversified demands to the participants of such a community, including LPP, are very useful when we think about how we can create positive learning environments for people of all kinds, including children and young people with special needs – who have often been marginalised by mainstream educational institutions. This could be people on the spectrum (autism spectrum disorder), people with mental health issues, or people who for different other reasons have had a hard time adjusting and fitting in. Often, people with these kinds of challenges face additional obstacles to their learning processes because they feel excluded and lonely, have experienced failure more often than success, and have no reason to have faith in the “system”. Because they have been challenged in the arena of social interaction, their ability to make use of social learning needs to be restored.

The task then, for practitioners of pedagogy and social education, is to enhance existing communities of practice, or in some cases to construct them. In order to create social circumstances in which teaching, and learning can take place, using elements from Lave and Wenger’s theories are useful, indeed.

Creating communities of practice

The issue of how to create an inclusive community where differently abled people can thrive and participate in a socially safe space and get involved with authentic activities is a real one. It is hard work. Often, when working with a group of young people who are challenged in different ways, pedagogy practitioners are faced with the reality that there are so many obstacles for getting an activity off the ground. An imaginary but realistic example:

“In the group that I teach we have eight youngsters. Today, we were supposed to go to the forest – it had been on the plan for weeks. This morning, I learned that one of the girls had to see her social worker for a status meeting. Another student was sick, a third one had to go to the dentist. A fourth one was upset about a message she had received from her mother and was unable to concentrate on anything else. Her friend, student number five, got involved in the family drama, and prioritised supporting her upset friend through the crisis – so she couldn’t overcome going anywhere either. We decided that my colleague would stay at home with the girls while they processed the family crisis. Student number six said he wouldn’t go if my colleague didn’t go – and the last two students were not in the mood of going anywhere, because “they didn’t want to go, when the rest of the group didn’t have to go.”

Arranged communities of practice can be traditions like “work weekends” where participants do gardening or maintenance work together.

One solution to overcome scenarios such as the one described above, at a school that caters for young people with psycho-social problems, is to create an intentional community of practice, focused on the planned activities. Participants in such an arranged learning community could be “old-timers” (settled students with previous experience), a group of volunteers, or “activity workers“ whose primary function is to ensure that the planned activity takes place, regardless of how many youth with special needs participate in the activities in the end.

To create an arranged community of practice of this kind, and make it succeed, we must ensure that everybody understands their role in the model.

“I am here to play football / cook / do gardening / paint / dance… together with whoever wants to join. I enjoy doing things together with others where we build our identities and share our humanity.” People with this attitude constitute the core of this community of practice. They understand that other, less socially able persons will participate when their mood and social circumstances allow them. They accept that tasks will be distributed according to ability, and not objectively fairly, and that some people will participate on their own terms – and that this is an example of legitimate peripheral participation.

A micro-community of practice: The Common Third

In Danish social pedagogy “the common third”, as described by philosopher Michael Husen, is a commonly used concept which is used about a range of activities, be it sports, arts, animal husbandry or exploring the big outdoors – hiking, mountain biking or sailing. It indicates that an activity is neither only the teachers’ / pedagogy practitioners’ project, nor an activity to please the pupil / child or young person, but something more and beyond. It is an activity or interest which enthuses and engages both of the parties – a common “third”.

A perfect “common third” is an equalising activity where the boundaries between who is the “teacher” and who is the “learner” are erased, because the activity demands the full attention of the practitioners involved – because everyone is struggling to keep up with the reality of the situation. As a result, they learn something new, together.

“A common third” allows us to share an activity in a way that we can both be equal, two people connected by something we both enjoy doing.

LPP theory in a nutshell

The key points Lave and Wenger emphasise in their ground-breaking book ”Situated learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation” are:

- Learners inevitably participate in communities of practice.

- To master knowledge and skills, newcomers become partial (peripheral) participants in an area they are trying to learn. In this participation, they interact with and learn from experts (full participants) and eventually develop into full participants themselves.

- Relationships elements between newcomers and old-timers include communities of knowledge and practice, artifacts, identities, activities, as individuals learn, they develop their knowledge, skills, and discourse.

“Communities of practice… are about knowing, but also about being together, living meaningfully, developing a satisfying identity, and altogether being human.”

~ Étienne Wenger

Communities of practice

”Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.”

”Note that this definition allows for, but does not assume, intentionality: learning can be the reason the community comes together or an incidental outcome of member’s interactions. Not everything called a community is a community of practice. A neighbourhood for instance, is often called a community, but is usually not a community of practice.”

Étienne Wenger – in “Introduction to communities of practice”, 1991

Situated Learning

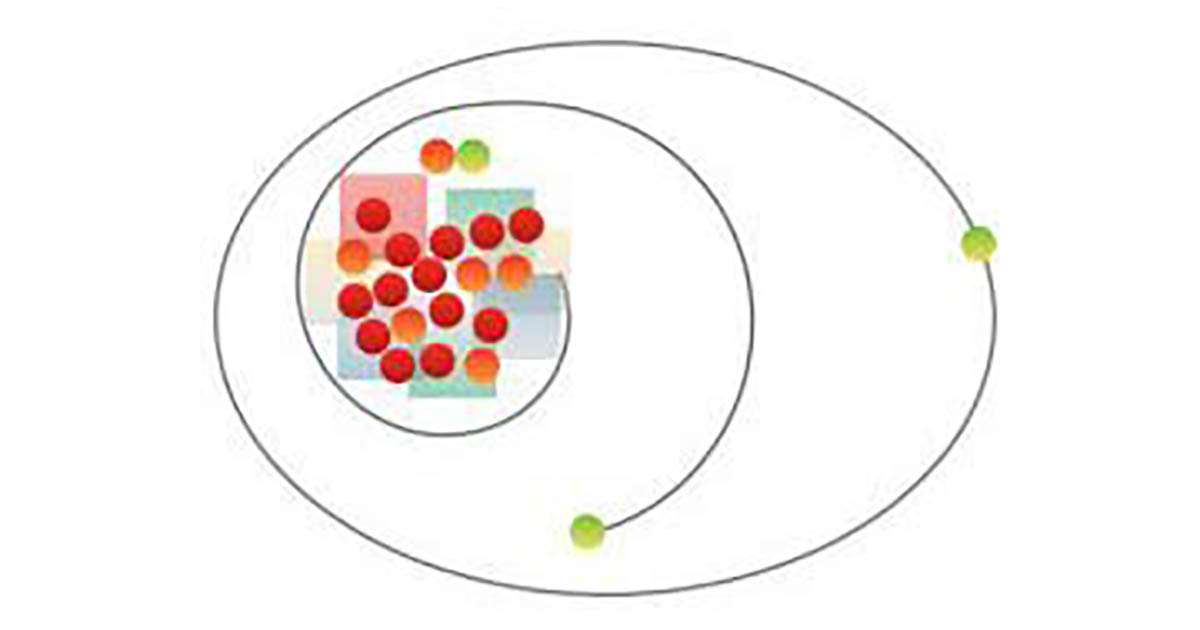

Situated learning is the process which “takes as its focus the relationship between learning and the social situation in which it occurs”. As learners gain experience and competence, they gradually move from an apprenticeship role to full participants in their community of practice.

Legitimate Peripheral Participation

Legitimate peripheral participation describes the journey that members of the same community of practice take together within their moving field of practice, even though their backgrounds and abilities vary. In the beginning newcomers enter the learning area as peripheral participants. Over time, they develop their knowledge, skill, and discourse moving from novices to experts, through legitimate practice, supported by the old-timers.

What is Pedagogy for Change?

The Pedagogy for Change programme offers 12 months of training and experiencing the power of pedagogy – while you put your skills and solidarity into action.

Studies and hands-on training takes place in Denmark, where you will work with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools with a non-traditional approach to teaching and learning.

In short:

• 10 months’ studies and hands-on training in Denmark, working with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools. At the same time yo will study the world of pedagogy with your team – a group of like-minded people. You will meet up for study days every month.

• 2 months of exploring the reality of communities in Scandinavia / Europe, depending on what is possible – pandemic conditions permitting. You will travel by bike, bus or perhaps on foot or sailing.

• Possibility to earn a B-certificate in Pedagogy.

MORE GREAT PEDAGOGICAL THINKERS

Paulo Freire

Freire’s pedagogy was originally developed for the oppressed adult illiterates of Brazil, but it also inspired teachers and social educators all over the world. Liberation & solidarity are key.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau wrote Émile, or On Education, 250 years ago – but the pedagogical principles described in this novel still have much to offer modern educators.

John Dewey

Education, teaching and discipline are lifelong social phenomena and conditions for democracy, according to acclaimed American philosopher John Dewey.

Anton Makarenko

Teaching, work, discipline & self-management were the main pillars in the pedagogy developed by Anton Makarenko. He became the founder of the theory of collective education.