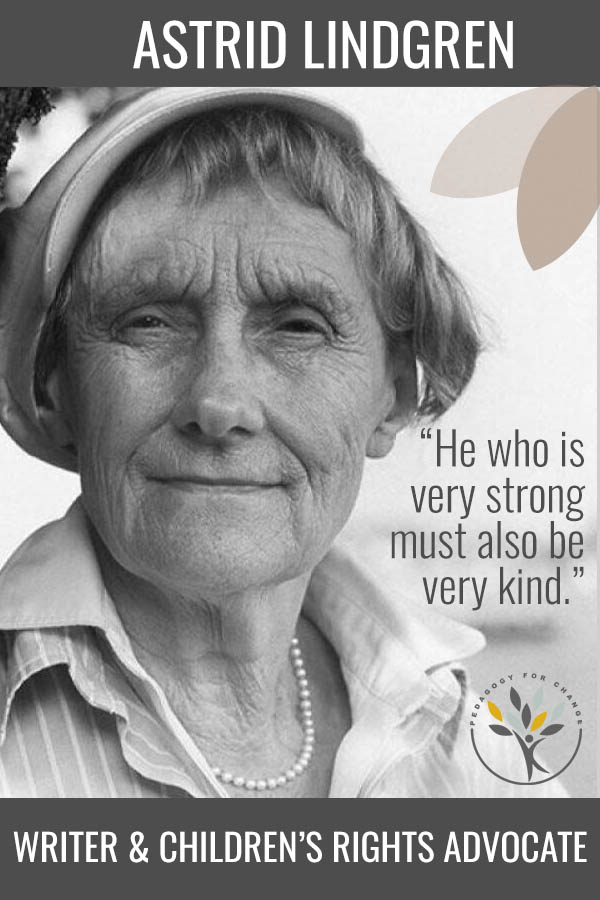

Astrid Lindgren

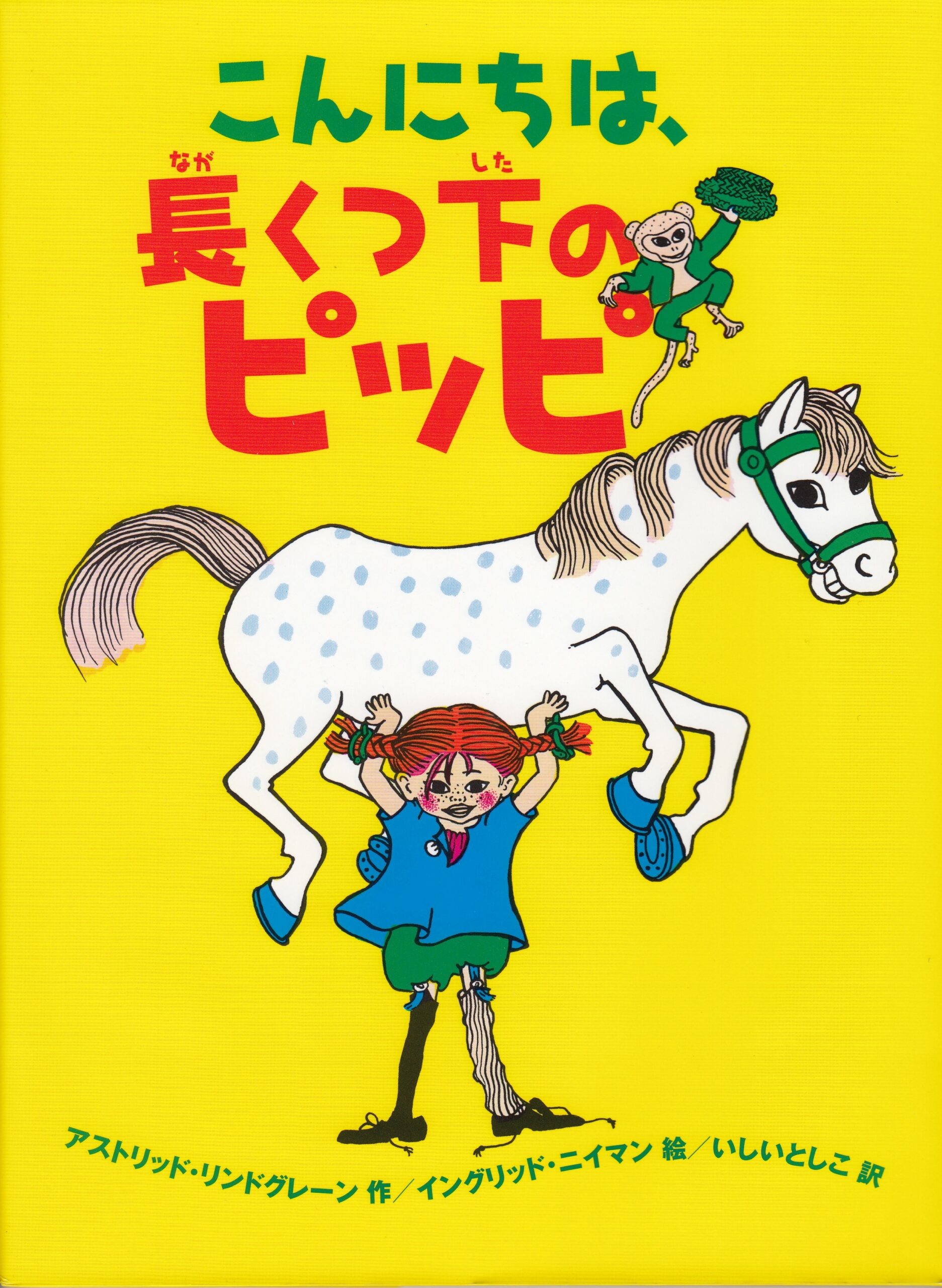

Swedish children’s book writer Astrid Lindgren published her first book about power girl Pippi Longstocking in 1946. Her thoughts about children were provocative then, and her approach to childhood as a phenomenon is progressive, even today.

Lindgren’s passion was storytelling. She never had ambitions to be an educator or spread ideas about pedagogy or child-rearing methods, but she wrote stories about children and childhood that have enlightened and inspired people worldwide. So, what is “Astrid Lindgren pedagogy”?

Astrid Lindgren grew up in the small town of Vimmerby and worked at a local newspaper when she fell pregnant, aged 18, in 1925. Due to the Christian patriarchal norms that permeated Swedish culture back then, Lindgren had no choice but to give birth to her son in faraway Copenhagen, the only place where she could do so without having to name the father – a married man. Moreover, she had to leave Lasse, her son, with foster parents in Denmark for the first three years of his life, because bringing up a child as a single mother was out of the question.

The trauma young Astrid experienced during those difficult years shaped her outlook on children and childhood. Having a child out of wedlock, being forced to leave her baby behind in a foreign country and witnessing the grief of her bewildered child who missed his Danish foster family when she could finally bring him back to her native Sweden, scarred her soul forever.

An ally of children

Looking back at this difficult time of her life, more than forty years later, Astrid Lindgren remembered how little Lasse cried inconsolably at being ripped from his home in Copenhagen and placed in completely new surroundings in Stockholm, with a mother that he hardly knew. Lasse, who understood that there was nothing he could do about the situation, resigned to his fate and wept in silence. He knew that he was at the mercy of the adults around him.

“That cry still cries within me and will stay with me for the rest of my days” noted Lindgren, concluding that Lasse’s muted weeping explained why she always has sided with the children in situations where adults make decisions about them that they cannot influence. “Adults assume that children can easily adapt. This is not the case even if it may look like they can. Children just capitulate to superior power.”

Children create their own destiny

Powerlessness is a fundamental condition for the protagonist children in Astrid Lindgren’s books. Not only because they oftentimes are poor, sick, orphaned, or lonely, but disenfranchised simply because they are children. However, Lindgren gives them a platform from where they can create their own destiny.

One example is Pippi Longstocking, who lives on her own, is the daughter of a pirate, has gold coins in a battered suitcase and can lift her horse above her head. Another example is Emil from Lönneberga, who has developed his own coping mechanism when he cuts one wooden figure after the other, while in solitary confinement in the firewood shed. And little “Skorpan”, the bedridden brother Lionheart, who defies his tuberculosis, joins his big brother in imaginary Nangijala to fight the mighty dragoness Katla. Lindgren’s child characters are fragile and strong at the same time, but above all, they have agency.

Loneliness and solitude

The children in Lindgren’s books are struggling with both internal and external problems. For example, we see fiercely independent children like Pippi and Emil face loneliness. Sometimes they choose solitude as an active choice, at other times it is an imposed reality. Emil can withdraw to the firewood shed and lock the door from the inside, too. It is not always a prison he is sent to by his father. Sometimes Emil enjoys being by himself.

Even power girl Pippi sometimes needs to withdraw from her fast and furious adventures. Sitting alone in the darkness in her Villa Villekulla home, she stares into the flames of a candle. What she is thinking about, we don’t know. In Lindgren’s stories, children are complex, multi-faceted people.

Rebels against oppression

Lindgren’s books are full of paradoxes. Imagination is used both as an escape from a harsh reality but is also a fun place to explore. Loneliness is an imposed circumstance but also a personal need. Lindgren’s stories are full of melancholy and authenticity which resonate with people all over the world who recognise her deep insights into the human condition.

Children can be rebels and in Lindgren’s stories, they fight against injustices and insist on their freedoms. They are not reduced to being adorable little rascals. Lindgren’s child protagonists have agency, and this novel approach to childhood earned Astrid Lindgren a reputation as a social critic. However, she remained a storyteller, above all.

A humanitarian storyteller

As a storyteller, Astrid Lindgren let her humanity shine through. She always sided with the children, but never condemned anybody. Sometimes, she would take the reader by the hand and explain something, for example, what a comet is. “Well, I am not sure that I myself know what it is”, she confesses and then goes on to give a wondrous description of the phenomenon. In this way, she is not afraid of showing her own vulnerabilities as a human.

Similarly, Lindgren doesn’t shy away from difficult subjects like death. Beloved grownups, pets, and even children, sometimes die in her books. In one of her darker stories, The Brothers Lionheart, subjects like serious disease, tyranny, betrayal, poverty, and death are explored, alongside hope, courage, love, and pacifism. The whole story is deliberately ambiguous about how much of the plot is real, keeping open the possibility that some of it could be hallucinations and fantasies experienced by the main protagonist, Skorpan, who is suffering from life-threatening pulmonary disease. The ending of the story is surprising for being a children’s book because it is open-ended. We don’t know if the protagonist makes it or not.

“Astrid Lindgren pedagogy”: Trust children

Later, Astrid Lindgren shared that she knew that the ending of the Brothers Lionheart was indeed controversial. To put people’s minds at rest, she contemplated adding an epilogue on the very last page to reassure the reader that the story ended happily but decided against it. She deemed it unnecessary. Lindgren had faith in the power of literature and in the essence of storytelling, but most of all she had faith in children.

Astrid Lindgren’s stories about the conditions children face and how they cope with power and injustices continue to inspire people worldwide. Today, Lindgren’s most famous book, the one about Pippi Longstocking, has been translated into 77 languages.

”If I ever had a particular intention with the Pippi character, apart from amusing my young audience, it was this: To show them that it is possible to have power without abusing it.”

– Astrid Lindgren

Bio: Astrid Lindgren

Children’s books writer, storyteller, screenwriter, editor, children’s rights activist.

Astrid Lindgren was born Astrid Anna Emilia Ericsson in Vimmerby, Sweden on 14 November 1907.

In 1994, Lindgren was awarded the Right Livelihood Award for “her unique authorship dedicated to the rights of children and respect for their individuality.” Her books have been translated to more than 200 languages.

Astrid Lindgren died in 2002, aged 94.

What is Pedagogy for Change?

The Pedagogy for Change programme offers 12 months of training and experiencing the power of pedagogy – while you put your skills and solidarity into action.

The training takes place in Denmark.

MORE GREAT PEDAGOGICAL THINKERS

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau wrote Émile, or On Education, 250 years ago – but the pedagogical principles described in this novel still have much to offer modern educators.

John Dewey

Education, teaching and discipline are lifelong social phenomena and conditions for democracy, according to acclaimed American philosopher John Dewey.

Anton Makarenko

Teaching, work, discipline & self-management were the main pillars in the pedagogy developed by Anton Makarenko. He became the founder of the theory of collective education.