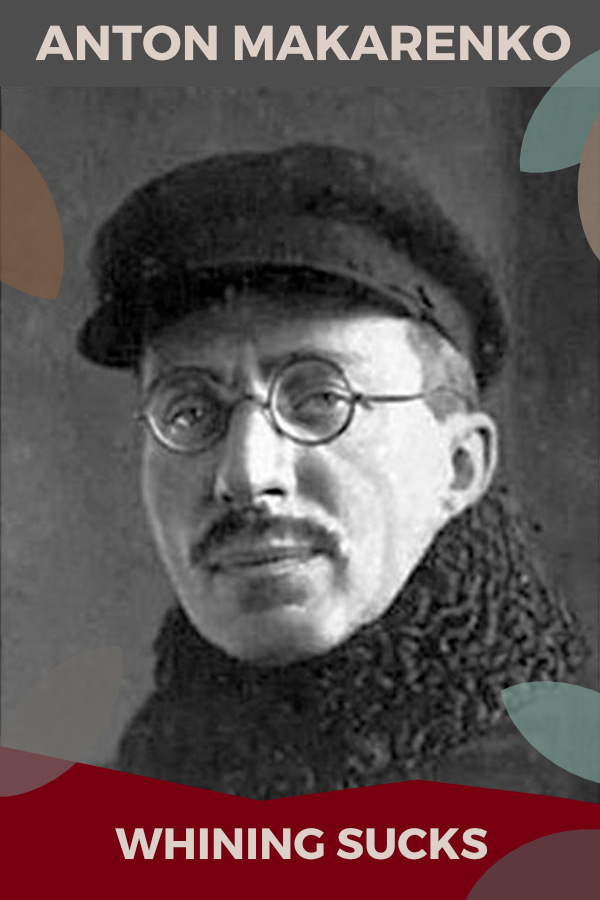

Anton Makarenko

Teaching, work, discipline and mostly self-management were the essentials of the pedagogic philosophy of Soviet citizen Anton Makarenko. He became the founder of the theory of collective education.

“It is not enough to improve humans. We must rehabilitate them. They are not to be made harmless members of society, but to be raised as active participants of the new times.”

This is what Soviet teacher and social educator Anton Makarenko concluded after he set to establish an orphanage for criminal and orphaned children. He himself was a sign of the times – an active teacher before, during and after the Russian revolution. He was a follower of Marxism and the leadership of Lenin and strongly inspired by the author Gorkij’s belief in humankind. Anton Makarenko was born in 1888 in Bilopillya, Ukraine which belonged to the Russian Empire at the time.

A new human

His goal was – as he put it – to create “the new human”. The Soviet citizen who would build the new Soviet Union without the use of a cane. He spent a lot of his life figuring out how to make that happen. And even though he was opposite of the benchmark of free upbringing and public authorities, he succeeded in re-disciplining 3.000 children and writing his masterpiece “The Pedagogical Poem”.

It has now been translated to more than 60 languages and has influenced the pedagogical way of thinking beyond the Soviet borders.

The third frontier

After the Russian revolution, there was a desperate need of teachers. Only one fifth of the adult Soviet citizens could read and write – and 80% of the children were not in school. So, a fiery pedagogical soul as Makarenko was in high demand. He was only 17 years old when he was hired as a teacher after just one year of studying pedagogy. At first as a private teacher with a noble family, which made him realise the depths of social injustices – and later at various schools.

Anton Makarenko began his pedagogical experimenting at an early stage of his career. He made school gardens, a school library, a school museum and children’s clubs. He created a children’s brass band and an evening school for the parents.

But it wasn’t until he was encouraged to make a residential institution for some of the two million homeless and criminal children in the 1920’s that his pedagogical ideas reallywere to be tested. The institution was named the Gorky Colony, after the great socialist realist Russian writer Maxim Gorky.

On Makarenko’s arrival, the buildngs were as neglected as the children living there. The problems of poverty ruled the day and the children were resentful and rude. They were larcenous and refused to work. With this “raw material” and under these circumstances the authorities expected Makarenko and his staff of teachers to create a “new human” – fitting into the socialist state. In addition, they would fight on the Third Front of the revolution by eradicating illiteracy, ignorance and superstition.

It was a difficult task. Later, Makarenko wrote that he never read as much pedagogical literature as in the first year of the Gorky Colony. However, it was the study of Lenin’s idea of schools and Maxim Gorky’s writings that in the end helped him keep confidence in mankind – and the project.

Ordinary children

Community, work and self-management were key points in Makarenko’s pedagogy. And his motto was: “No whining!” He was convinced that the child’s personality was to evolve in the interaction with others. When “his” children were anti-social, it wasn’t because of a moral deficiency in the children’s personality, but rather a reflection of a dysfunctional contact between the children and the society in which they had been living. They were a procuct of the circumstances they had been born into.

“Society and upbringing cannot be separated. In reality, they are ordinary children, whose fate has put them in a completely foolish situation,” Makarenko pointed out.

An alternative community

As an alternative, Anton Makarenko built a community where they not only lived, but also worked together. Each student was supported in their individual and versatile development.

The everyday life of the children consisted of four hours of school, four hours work and then a meaningful and cultural spare time. Makarenko demanded that the students were given ten years of school, though the norm outside the colony was only seven years.

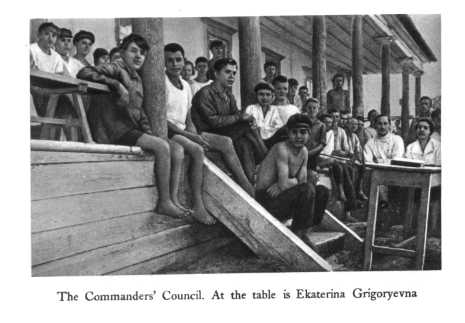

In the beginning, it was the teachers who planned the activities, but soon Makarenko made it more student-led. He was a great proponent of autonomy of the collective. The youngsters in the colony were divided into departments with variable students as leaders. The department leaders were in the commanding council and participated in all decisions.

The goal was not only to promote teamwork, helpfulness, tolerance and understanding that you can achieve more together. It was also an education in democracy where the children in the colony learned how to lead, organise and manage – and to be subordinate.

Makarenko’s legacy

Makarenko’s student-democracy and his practice of four hours of daily studies and ten years of school offended the surrounding communities. Nonetheless, Makarenko was not to be ignored. He succeeded in re-disciplining thousands of children into active, social and beneficial citizens. First in the Gorky Colony and later at the orphanage Dzierzinsky Labour Commune.

Makarenko can thank author Maxim Gorky for becoming world renowned. “A teacher in life”, Makarenko called him. It was Gorky, who first printed Makrenko’s “A Pedagogical Poem”. A masterpiece that also became important in Danish pedagogy in the 1970s.

In 1988 UNESCO considered that Makarenko was one of four educators who determined the world’s pedagogical thinking of the 20th century. The others were John Dewey, Georg Kerschensteiner, and Maria Montessori.

“It is not enough to improve humans. We must rehabilitate them.

They are not to be made harmless members of society,

but to be raised as active participants of the new times.”

~ Anton Makarenko

Social Pedagogy in Denmark

Scandinavian social pedagogy is known for its holistic practice which combines “head, heart and hands” – theory, empathy, and practice. A core value is respecting the individual’s rights.

Learning through theatre

Theatre is an important pedagogical tool which provides an opportunity for us to explore realms and realities outside of the classroom, without having to travel.

Artful expression in pedagogy

Art is a pedagogical tool which provides an opportunity for everyone to work with open-ended solutions rather than striving for conventional error-free essays or science reports.

What is Pedagogy for Change?

The Pedagogy for Change programme offers 12 months of training and experiencing the power of pedagogy – while you put your skills and solidarity into action.

Studies and hands-on training takes place in Denmark, where you will work with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools with a non-traditional approach to teaching and learning.

In short:

• 10 months’ studies and hands-on training in Denmark, working with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools. At the same time yo will study the world of pedagogy with your team – a group of like-minded people. You will meet up for study days every month.

• 2 months of exploring the reality of communities in Scandinavia / Europe, depending on what is possible – pandemic conditions permitting. You will travel by bike, bus or perhaps on foot or sailing.

• Possibility to earn a B-certificate in Pedagogy.

MORE GREAT PEDAGOGICAL THINKERS

Paulo Freire

Freire’s pedagogy was originally developed for the oppressed adult illiterates of Brazil, but it also inspired teachers and social educators all over the world. Liberation & solidarity are key.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau wrote Émile, or On Education, 250 years ago – but the pedagogical principles described in this novel still have much to offer modern educators.

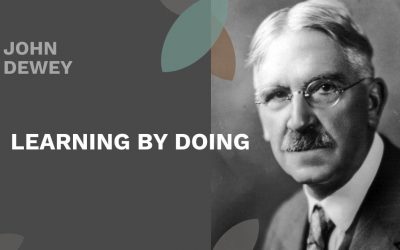

John Dewey

Education, teaching and discipline are lifelong social phenomena and conditions for democracy, according to acclaimed American philosopher John Dewey.