Axel Honneth · Recognition in Pedagogy

We all need recognition – to be seen, heard, and acknowledged. We crave this recognition from loved ones, of course, but we also need recognition from entities like the State, because it secures our constitutionally protected rights, as citizens. In our professional life, we also enjoy when our work is appreciated, and when we feel acknowledged as valued colleagues. In the absence of recognition, we suffer, unloved and unseen.

In social pedagogy, a “recognising approach” is useful as a foundational principle.

Recognition in Danish social pedagogy

In the Danish social pedagogy tradition, “anerkendende pædagogik” – a pedagogy of recognition – has been the norm for decades. Among the thinkers who have inspired this approach are two Norwegians, psychologist Anne-Lise Løvlie Schibbye and pedagogue Berit Bae, but also philosopher Axel Honneth, a German-born philosopher from the so-called Frankfurt School tradition of social theory.

Axel Honneth has focused his energies on the idea of recognition. His “theory of recognition” provides a valuable framework for how we can create conditions in which people feel validated as human beings – and this is paramount in the world of social pedagogy.

Recognition as an overarching approach in social work

When working with people who have experienced neglect and rejection in their lives, practitioners of social pedagogy understand that recognition is an important tool.

It’s about seeing people and letting them know that you do. A smile, a nod or a friendly pat on the back can make someone’s day. It’s about listening to people and being curious about what you hear, instead of jumping to conclusions. It’s about validating someone’s emotions, even though you cannot fully empathise. Over time, this practice of recognition means that we can build meaningful relationships with the people we support – and ultimately cultivate social inclusion.

Axel Honneth’s theory of recognition

Axel Honneth describes humans as beings that constantly seek recognition. In his famous theory of recognition, he argues that recognition is necessary for how we humans maintain a good relationship with ourselves, and for how we develop our identity.

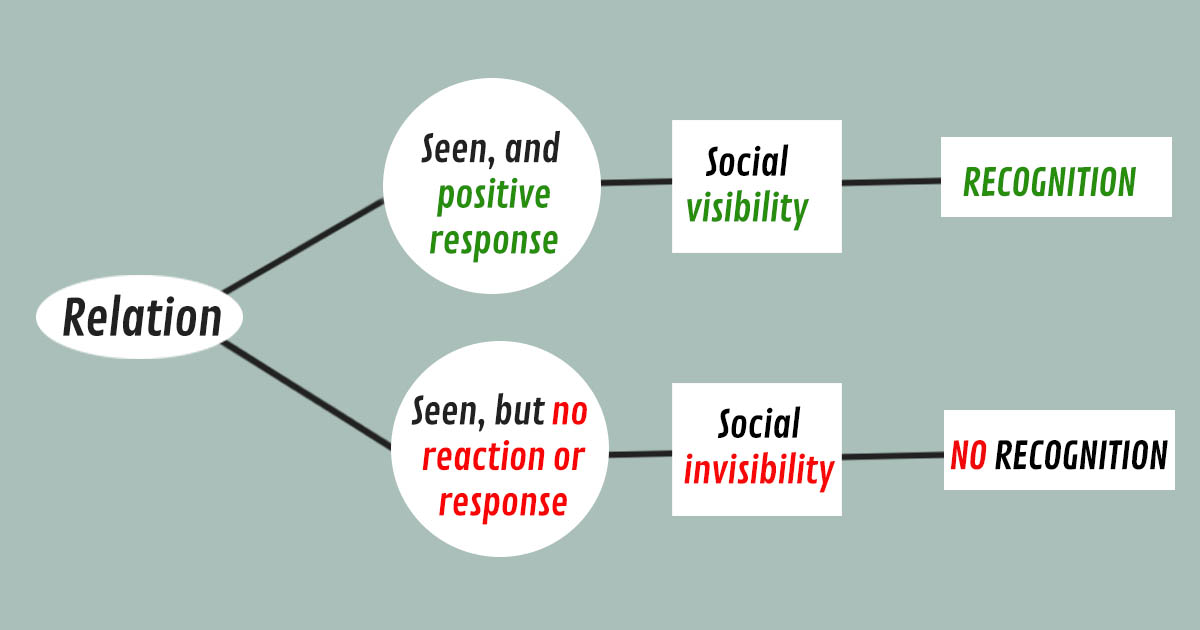

To achieve recognition, someone needs to do the actual recognising. In other words: relationships of different kinds are fundamental. These relationships can be interpersonal, between two people, but they can also be within groups or communities. According to Honneth, relationships can be visible or invisible.

Honneth states that the relation, and a positive response from the other, the counterpart, need to be present to achieve recognition. An example:

At a lively family dinner, you wish to share the good news that you have passed an important exam. It can go both ways: Perhaps your statement is immediately picked up, noticed, and followed up with positive attention: “Wow – that’s great! Well done!”

However, sometimes it goes horribly wrong. For example, when your boisterous uncle seizes the moment when you say “exam”, to loudly exclaim how he remembers an exciting story about how he managed to get top marks in an exam through a creative cheating scheme. Your uncle’s story gets all the attention, and your piece of positive news is completely drowned out in the ensuing laughter and additional stories of your family’s school days. Your success story has gone unnoticed, and you haven’t achieved any recognition.

Another disappointing scenario: Instead of being acknowledged for having passed the exam, you are met with inquiries about which grade you got and questions like “why on earth didn’t you get top marks?” Again: your success is ignored and not recognised by people who are important to you. We all know the feeling. It’s horrible. When we as practitioners of social pedagogy apply a recognising approach in our work, we hope to protect the people we look after from such negative emotions.

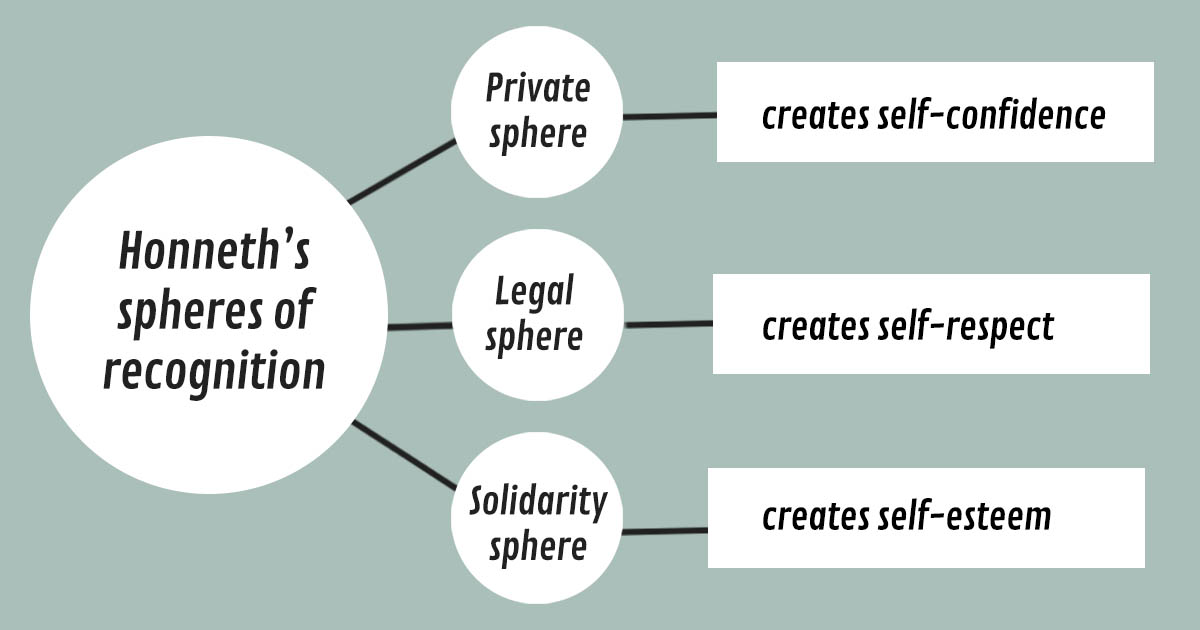

Spheres of recognition and self-relation

Axel Honneth’s theory of recognition operates in three spheres: The private sphere, the legal sphere, and the sphere of solidarity. In addition to the different spheres of recognition, Honneth describes three levels of relationship that an individual can have with themselves: self-confidence, self-respect and self-worth.

According to Honneth, self-confidence is achieved when individuals recognise for themselves their physical needs and desires and can articulate them to themselves and others. This means being able to assert oneself confidently about physical needs and desires. “Yes, please – a cup of tea would be great. White, no sugar.”

A second level, self-respect, exists when individuals recognise their own moral accountability and the value of their personal judgment. This means being able to stand your ground, even when your opinion is unpopular. “I disagree with you. In my opinion, the death penalty can never be justified.”

The third level, what Honneth refers to as self-worth and what is often referred to as self-esteem, is achieved when individuals recognise and celebrate the certainty of their own capabilities and positive qualities. “Sure, I can fix the brakes on this tractor and have it fully functional by Friday, no problem.”<

Which level of self-relation a human being can achieve, depends on the experience they’ve had in the three spheres of recognition. The more positive feedback and recognition we’ve had in our lives, the higher degree of self-appreciation we enjoy.

Love is a precondition for self-confidence

In the first sphere, the private sphere of recognition, family and friends are key. Self-confidence develops when we are recognised by ”significant others” – meaning receiving lots of love, attention and care. We experience that we are treated as valuable, unique human beings and that our needs and desires are taken seriously. In short: if we are recognised in the private sphere during our childhood, we develop self-confidence.

Thus, love is a precondition for self-confidence and the precondition for love is the ability to form relationships. The inability to form meaningful relationships is a great obstacle in a person’s development. Individuals who grow up in dysfunctional families are likely to miss out on love, care, and recognition, and will struggle with self-confidence issues which will have an adverse effect on their well-being.

Therefore, most modern societies understand that it’s a good idea to secure that all citizens receive a basic level of care. Social legislation is put in place, for example provisions like foster homes or care homes for children and youth who are not adequately looked after by their families. Providing attention, care and recognition then becomes the task of social pedagogy practitioners who work with these children and youth.

Express yourself and belong somewhere

In the second sphere, the legal sphere, Honneth argues that recognition is achieved through democratic principles, like equality before the law. For example, all citizens, regardless of their background, are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. If a person achieves recognition in this sphere, they will respect and recognize themselves, and self-respect will follow. Similarly, a school which promotes freedom of expression will foster individuals who can express their views with confidence.

In the third sphere, where solidarity is the key, recognition is experienced in collective settings and by participating in the wider community. Self-esteem emerges from the gaze and recognition of others who acknowledge one’s capabilities and qualities as making a valuable contribution to a group, collective or community. Honneth describes a sense of community solidarity – a sense of well-being founded on respect and recognition of the contribution being made to achieve common goals, with like-minded people.

Pedagogy of Recognition

If we, as individuals, fail to be recognised in the private, legal and community spheres, we risk losing our self-relation, to the detriment of our personal and social development. In this light, being part of a community with like-minded people can be of utmost importance, because we can receive the recognition that we need.

However, being part of a group of people who share values and goals doesn’t necessarily mean that you will magically receive recognition. It is possible to be part of a community, without feeling included or recognised. Feeling alienated and lonely is a problem expressed by many young people.

Making communities work and fostering a healthy atmosphere where everyone feels seen, heard, respected, liked, included, and recognised is therefore one of the most important tasks that practitioners of social pedagogy have. That’s why we can use the theory of recognition in social pedagogy.

Sawubona – "I see you"

The most common greeting in the Zulu language is ”Sawubona”. It literally means “I see you. You are important to me and I value you”.

It’s a way to make the other person visible and to accept them as they are with their virtues, nuances, and flaws. In response to this greeting, people usually say with “shiboka”, which means “I exist for you”.

If we, as individuals, fail to be recognised in the private, legal and community spheres, we risk losing our self-relation, to the detriment of our personal and social development. In this light, being part of a community with like-minded people can be of utmost importance, because we can receive the recognition that we need.

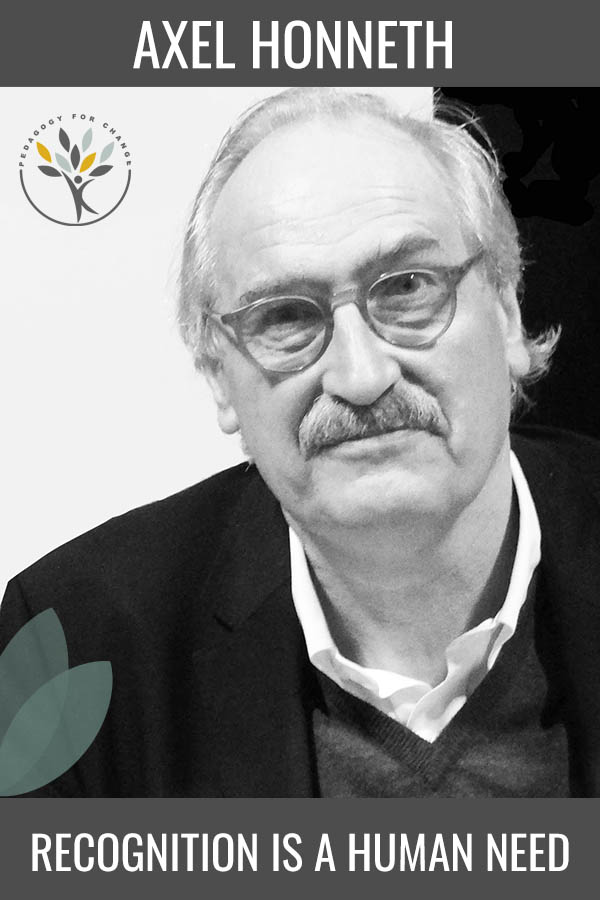

Bio: Axel Honneth

Axel Honneth is a German philosopher educator and writer. He is a professor at Columbia University and at the University of Frankfurt. Honneth is the author of such books as The Critique of Power, Freedom’s Right and Struggle for Recognition – the Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts.

What is Pedagogy for Change?

The Pedagogy for Change programme offers 12 months of training and experiencing the power of pedagogy – while you put your skills and solidarity into action.

The training takes place in Denmark.

MORE GREAT PEDAGOGICAL THINKERS

Astrid Lindgren

Astrid Lindgren’s thoughts about children were provocative in the 1940s, and her approach to childhood as a phenomenon is progressive, even today.

Lev Vygotsky

Interaction with peers, imitation, collaborative learning and other social interaction is key to how the human mind develops, according to Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky.

Maya Angelou

In times of injustice and hardship, Maya Angelou’s call for humanity, unity and resilience teaches us many important life lessons. Her works inspire hope through action.

James P. Comer

“No significant learning can occur without a significant relationship.” Really? Does Dr. James Comer mean that students need to be close to their teacher to learn something?

Jean Lave

Jean Lave is a social anthropologist and learning theorist who believes that learning is a social process, as opposed to a cognitive one – challenging conventional learning theory.

Søren Kierkegaard

Making choices and taking action are at the very core of existentialism. By taking on these responsibilities, as human beings – we find the meaning of life.

Maria Montessori

Children prefer to work, not play. This is one of the main ideas of Maria Montessori, a trailblazers of early childhood education. “The child who concentrates is immensely happy” she noted.

Sofie ‘Rif’ Rifbjerg

Brought up in the countryside Sofie Rifbjerg knew intuitively that fresh air, free play & a deep respect for children’s own agency was paramount for their positive development.

Paulo Freire

Freire’s pedagogy was originally developed for the oppressed adult illiterates of Brazil, but it also inspired teachers and social educators all over the world. Liberation & solidarity are key.